Twice a day the tide goes out revealing a shoreline studded with pools and draped with seaweed. Although the more mobile animals will have moved down with the tide, some will be trapped in rockpools. These act as natural aquariums giving a miniature reflection of what the entire coastline is like when the tide is high. Those animals that are stuck to the rocks will have closed up tight against the drying air or will be hiding under the moist seaweeds, which have flopped against the rocks.

Seaweeds

Seaweeds are the marine equivalent of grasses, bushes and trees. However seaweeds belong to a simple group of plants called algae and unlike most land plants they do not have roots, but instead have a structure called a holdfast. As the name suggests this attaches the seaweed strongly to the rocks but it is not used to absorb water or nutrients.

Seaweeds are the marine equivalent of grasses, bushes and trees. However seaweeds belong to a simple group of plants called algae and unlike most land plants they do not have roots, but instead have a structure called a holdfast. As the name suggests this attaches the seaweed strongly to the rocks but it is not used to absorb water or nutrients.

Seaweeds come in come in many different shapes, sizes and colours. They can be found in distinctive zones between the high and low water marks. Each species is adapted to survive the particular levels of exposure which include changes in salinity, light, humidity and temperature found within its zone.

The easiest species to identify are a family of brown seaweeds known as Wracks. They each occupy specific zones on the seashore and once you have learnt to identify each member of the family you can work out which zone you are in on the shore.

Many different animals eat seaweeds, others hide amongst the fronds (or leaves) and some live attached to them. While seaweed offers the perfect cover for seashore animals it also has several other uses that you may not be aware of. Seaweeds are used to help make lots of things for example ice cream, jelly, toothpaste, beer and dyes.

Sponges

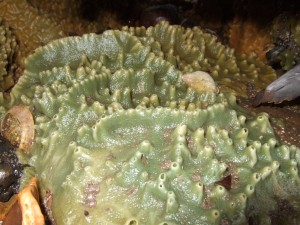

Sponges are very simple animals; they live in colonies, have no obvious body parts and often just look like a spongy mass encrusting a rock. They live under stones, in rock pools or on the underside of overhanging rock ledges where it is damp and shaded from direct sunlight.

The breadcrumb sponge is the most common sponge found on the shore. It is flat and can be found in various colours but most commonly green or orange. On its surface the breadcrumb sponge has a number of large holes which look like miniature volcanoes. The sponge draws in water through these holes which it filters for minute food particles and oxygen. This water is then pushed out through more numerous but much smaller holes that are difficult to see.

The breadcrumb sponge is the most common sponge found on the shore. It is flat and can be found in various colours but most commonly green or orange. On its surface the breadcrumb sponge has a number of large holes which look like miniature volcanoes. The sponge draws in water through these holes which it filters for minute food particles and oxygen. This water is then pushed out through more numerous but much smaller holes that are difficult to see.

The sponges you can find on the shores of Scotland are related to the large sponges which were used in the bath and which live in warmer water in the tropics. Too many of these have been collected and now most bath sponges are man-made.

Sea Anemones

Although they may look like flowers, sea anemones are actually animals closely related to jellyfish. The structures that look like flower petals are actually tentacles armed with deadly stinging cells, which are used to catch and paralyse their food. The anemone waves its tentacles around in the water, if they touch a prey item this triggers tiny poisoned darts on a thread which shoot out and paralyse the prey. They then retract these tentacles and pull the food into their mouths. The beadlet anemone is the one most commonly found on the shore and it occurs all around Britain. It is usually red or green with a ring of blue dots at the base of its tentacles and lives firmly attached to rocks. The tentacles are very sensitive and can be drawn back very quickly when touched. This is so that the anemones can stop small fish nipping them off!

Although they may look like flowers, sea anemones are actually animals closely related to jellyfish. The structures that look like flower petals are actually tentacles armed with deadly stinging cells, which are used to catch and paralyse their food. The anemone waves its tentacles around in the water, if they touch a prey item this triggers tiny poisoned darts on a thread which shoot out and paralyse the prey. They then retract these tentacles and pull the food into their mouths. The beadlet anemone is the one most commonly found on the shore and it occurs all around Britain. It is usually red or green with a ring of blue dots at the base of its tentacles and lives firmly attached to rocks. The tentacles are very sensitive and can be drawn back very quickly when touched. This is so that the anemones can stop small fish nipping them off!

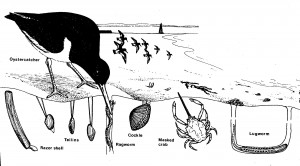

Worms

Worms are very common animals on the shores of the Marine Reserve. There are many different shapes and sizes and many, like lugworms and ragworms are difficult to see as they live their lives out underground. Lugworms live in a U-shaped burrow in the sand with a hole at one end of the burrow and a mound of coiled sand at the other end. The coiled worm cast is the only sign of its presence. Ragworms also live buried in the sand but they leave no sign of themselves on the surface. You will need to dig in the sand to try to find them.

Worms are very common animals on the shores of the Marine Reserve. There are many different shapes and sizes and many, like lugworms and ragworms are difficult to see as they live their lives out underground. Lugworms live in a U-shaped burrow in the sand with a hole at one end of the burrow and a mound of coiled sand at the other end. The coiled worm cast is the only sign of its presence. Ragworms also live buried in the sand but they leave no sign of themselves on the surface. You will need to dig in the sand to try to find them.

Bootlace and sandmason worms are slightly easier to find. Bootlace worms can be found in muddy gravel underneath stones on the shore. As their name suggests they are long and thin and black – in fact they can reach up to 5 metres in length. Sandmason worms build fragile tubes by sticking grains of sand together. These distinctive tubes can be found sticking a few centimetres out of gravelly sand at low tide.

Sea Snails

Many different species of sea snail are found on the shores of the Marine Reserve. Some live in cracks in the rocks, some under boulders or in rock pools and others on seaweed. Most of the snails you find on the shore have spiral shells. The commonest of these is the edible periwinkle, known locally as a whelk. When you pick up a shell with a snail inside it hides by drawing itself into the shell, closing the entrance with a horned plate called an operculum. This operculum acts a bit like a trap door when the tide goes out, sealing the snail inside the shell away from predators and preventing it from drying out. If left alone they will come out of their shells and begin to move about.

Many different species of sea snail are found on the shores of the Marine Reserve. Some live in cracks in the rocks, some under boulders or in rock pools and others on seaweed. Most of the snails you find on the shore have spiral shells. The commonest of these is the edible periwinkle, known locally as a whelk. When you pick up a shell with a snail inside it hides by drawing itself into the shell, closing the entrance with a horned plate called an operculum. This operculum acts a bit like a trap door when the tide goes out, sealing the snail inside the shell away from predators and preventing it from drying out. If left alone they will come out of their shells and begin to move about.

The limpet is a snail with a cone shaped shell, which can be found stuck to rocks all over the shores of the Marine Reserve. They hold on using a large muscular foot so that the waves do not wash them away even in the stormiest conditions. When the tide is out they clamp down tightly onto the rocks ensuring that the animal does not dry out. When the tide is in limpets glide about on the rocks feeding by using their long, file like tongues to scrape off tiny plants. You can sometimes see the feeding trail of the limpets as a zigzag pattern on rocks. After feeding each limpet will return to the place in the rock where it set out. A limpet can live for many years and it always returns to the same point. Over the years it makes an oval mark on the rock known as a ‘home scar’.

The limpet is a snail with a cone shaped shell, which can be found stuck to rocks all over the shores of the Marine Reserve. They hold on using a large muscular foot so that the waves do not wash them away even in the stormiest conditions. When the tide is out they clamp down tightly onto the rocks ensuring that the animal does not dry out. When the tide is in limpets glide about on the rocks feeding by using their long, file like tongues to scrape off tiny plants. You can sometimes see the feeding trail of the limpets as a zigzag pattern on rocks. After feeding each limpet will return to the place in the rock where it set out. A limpet can live for many years and it always returns to the same point. Over the years it makes an oval mark on the rock known as a ‘home scar’.

Some sea snails such as mussels have two halves to their shells and feed by filtering the water for tiny plants and animals called plankton.

Crabs & their Relatives

There are three common species of crab found on the Marine Reserve shores. The green shore crab is the easiest to find hiding under weed, in crevices or in the many rockpools. It is most commonly green in colour and has a saw-tooth edge to the shell. The edible crab found less often but is just as easily identified being reddish-brown, with a piecrust edge to the shell and black tips to its pincers.

There are three common species of crab found on the Marine Reserve shores. The green shore crab is the easiest to find hiding under weed, in crevices or in the many rockpools. It is most commonly green in colour and has a saw-tooth edge to the shell. The edible crab found less often but is just as easily identified being reddish-brown, with a piecrust edge to the shell and black tips to its pincers.

You may quite often come across what appear to be dead crabs but which are in fact their old discarded shells. Having a hard skeleton on the outside of the body means that crabs must cast off this shell to grow. Under the old shell is a new one which is very soft for a few days. This crab temporarily pumps itself up with water to stretch this shell so that when it hardens there is room inside for the crab to grow.

You may quite often come across what appear to be dead crabs but which are in fact their old discarded shells. Having a hard skeleton on the outside of the body means that crabs must cast off this shell to grow. Under the old shell is a new one which is very soft for a few days. This crab temporarily pumps itself up with water to stretch this shell so that when it hardens there is room inside for the crab to grow.

The third common crab of the shore is the hermit crab which is different from the others as it has a very soft body and so requires another shell for protection. Snail shells left vacant by the original occupants are used. As the hermit crab grows it will have to find a larger shell and will sometimes fight with another hermit crab to steal its shell.

When you are exploring the seashore you will notice some rocks are covered in small white volcanoes. These are barnacles – close relatives of crabs. Barnacles begin their life in the sea as minute floating larvae making up part of the plankton. In an amazing underwater transformation the larvae settle out on any available surface and develop into the adult, volcano-shaped form. The adult barnacles are glued to the rock by their heads where they live out the rest of their lives. When covered with water, they open two little doors in the top of the shell and stick their feathery legs out to capture food particles.

When you are exploring the seashore you will notice some rocks are covered in small white volcanoes. These are barnacles – close relatives of crabs. Barnacles begin their life in the sea as minute floating larvae making up part of the plankton. In an amazing underwater transformation the larvae settle out on any available surface and develop into the adult, volcano-shaped form. The adult barnacles are glued to the rock by their heads where they live out the rest of their lives. When covered with water, they open two little doors in the top of the shell and stick their feathery legs out to capture food particles.

Spiny Skinned Animals

The echinoderms, or spiny-skinned animals are a group of animals found only in the sea. The best known are starfish and sea urchins and these can be found on the rocky shores of the Marine Reserve in rockpools or under stones. The upper surface of starfish and sea urchins is covered by spines and so rough to touch. The body is divided into five segments and in the starfish these are seen as arms. Sometimes a starfish may lose an arm or two if attacked by a predator but they can grow these back. They move around using many hundreds of tiny, sucker-like, tube feet. Starfish have their mouth on their under surface and feed by exuding their stomach over their prey and dissolving it before sucking it up.

The echinoderms, or spiny-skinned animals are a group of animals found only in the sea. The best known are starfish and sea urchins and these can be found on the rocky shores of the Marine Reserve in rockpools or under stones. The upper surface of starfish and sea urchins is covered by spines and so rough to touch. The body is divided into five segments and in the starfish these are seen as arms. Sometimes a starfish may lose an arm or two if attacked by a predator but they can grow these back. They move around using many hundreds of tiny, sucker-like, tube feet. Starfish have their mouth on their under surface and feed by exuding their stomach over their prey and dissolving it before sucking it up.

Sea urchins graze on young kelp and other organisms living on the rock surface using specially adapted teeth on the underside of their bodies. They have a round shell called a test which is covered in hard spines for protection. Like starfish, sea urchins also have tube feet which they use for movement and which they also use to stick pieces of seaweed over their shells to act as camouflage.

Sea urchins graze on young kelp and other organisms living on the rock surface using specially adapted teeth on the underside of their bodies. They have a round shell called a test which is covered in hard spines for protection. Like starfish, sea urchins also have tube feet which they use for movement and which they also use to stick pieces of seaweed over their shells to act as camouflage.

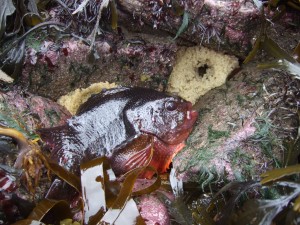

Shore Fish

There are many different species of fish to be found in the sea of the Marine Reserve. Some species prefer living in the shallow water which covers the shore areas when the tide is in. When the tide goes out they either hide in rockpools or lie under stones where there is enough water trapped to keep them damp until the tide comes back in.

The commonest fish found on the shore are the shanny and the butterfish. These are often found hiding under stones or dense seaweed when the tide is out. When they are uncovered they are able to wriggle away very quickly and are difficult to catch without a net.

The commonest fish found on the shore are the shanny and the butterfish. These are often found hiding under stones or dense seaweed when the tide is out. When they are uncovered they are able to wriggle away very quickly and are difficult to catch without a net.

Fish that can be found in rockpools when the tide is out include scorpion fish, 15-spined sticklebacks, rocklings, sea snails and occasionally, the male lumpsucker. Up to about 30 centimetres in length, this bulbous, fleshy-lipped fish is one of the more colourful and bizarre inhabitants of the North Sea. In springtime they move inshore to breed and the male adopts his breeding colours – anything from pink with black dots to yellow with red fins and lips. Once the female has secured her egg mass into a suitable crevice the male fertilises them. He then clamps himself to the rock next to the eggs with a large sucker on his underside and stands guard for several weeks, fending off any potential predators until the eggs hatch. The lumpsucker is so dedicated to guarding the eggs that even at extreme low tides when they will be uncovered by the water for 30 minutes or so he remains with them, exposed to the air for a short amount of time.

On sandy shores, particularly around the low water mark, if you walk though the shallow water you may disturb juvenile flat fish or spot sandeels diving into the sand for cover.